The concept of reincarnation, or the rebirth of a soul in a new body, has been a subject of fascination and theological debate across various religions. Today, we will be having a look at what the Bible and related Jewish and Christian teachings say about reincarnation, contrasting it with the more widely accepted notions of resurrection and the afterlife within these traditions.

We explore the scriptural interpretations, the influence of Kabbalistic thought, and the broader cross-cultural beliefs that have shaped the understanding of the soul’s journey beyond death.

Key Takeaways

- Reincarnation is not explicitly mentioned in the Hebrew Bible or New Testament, but is a central tenet in Kabbalistic Jewish mysticism known as Gilgul neshamot.

- Christian doctrine traditionally rejects reincarnation, emphasizing the immortality of the soul, final judgment, and the singular event of resurrection through Jesus Christ.

- Medieval Jewish philosophers largely dismissed reincarnation, considering it a non-Jewish belief, despite its later centralization in the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria.

- Cross-cultural beliefs, such as those of the ancient Egyptians and Chinese, have contributed to diverse concepts of the soul and its journey after death.

- The Bible offers various accounts of resurrection, which are distinct from reincarnation, including the resurrections of Jesus and other biblical figures.

Biblical Perspectives on the Afterlife and Resurrection

Hebrew Bible and Rabbinic Literature

The Hebrew Bible, also known as the Tanakh, is central to Jewish religious life and thought. It comprises three parts: the Torah, Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). Rabbinic literature further explores and interprets these texts, providing a rich tapestry of theological and ethical guidance.

- Torah

- Nevi’im

- Ketuvim

Rabbinic literature, including the Mishnah, Talmud, and Midrash, delves into the complexities of the Hebrew Bible. These texts are foundational to understanding Jewish law, philosophy, and mysticism.

The concept of an afterlife is more implicit than explicit in these writings, with more focus on the present life and the obligations within it.

The mystical traditions within Judaism, such as Kabbalah, draw upon these sacred texts to elucidate deeper spiritual meanings and the hidden aspects of the Torah. The esoteric teachings of the Kabbalah, including the Zohar, offer a unique perspective on the journey of the soul, hinting at cycles of growth and transformation that could be interpreted as aligning with the idea of reincarnation.

New Testament Accounts of Resurrection

The New Testament narratives present various accounts of resurrection, most notably the central Christian claim of Jesus’ resurrection. This event is not isolated; the scriptures recount the revivals of Lazarus, Jairus’ daughter, and the young man of Nain, as well as the many who rose at Jesus’ crucifixion.

Curiously, those who witnessed the risen Jesus often did not recognize him immediately. Instances include Mary Magdalene mistaking him for a gardener and the disciples on the road to Emmaus only realizing his identity upon the breaking of bread.

Even among his closest followers, there were doubts about the authenticity of these appearances, suggesting a complex interplay between physical and spiritual recognition.

Visions also play a significant role in the New Testament’s depiction of the resurrected Jesus. Stephen, before his martyrdom, envisions Jesus at the right hand of God, and the Book of Revelation describes encounters with Christ in a visionary state.

These accounts raise intriguing questions about the nature of these post-resurrection interactions.

The narrative of Jesus’ resurrection concludes with his ascension to heaven, an event detailed in the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles. This moment signifies the transition from his earthly ministry to a spiritual existence, promising eternal life to believers and setting the stage for the spread of his teachings through his disciples.

Contrasting Eternal Life and Reincarnation

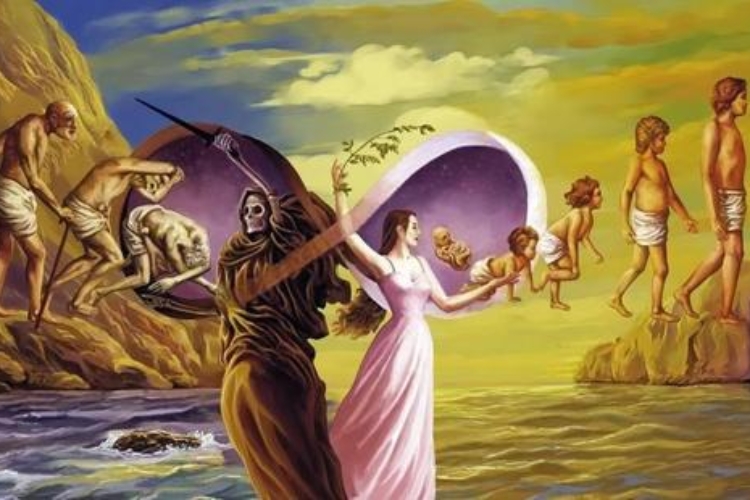

The concept of eternal life in the Bible is often juxtaposed with the idea of reincarnation, which is not explicitly supported by the biblical texts. Eternal life is typically understood as a singular, unending existence in the presence of God, whereas reincarnation suggests a cyclical process of death and rebirth.

- Eternal Life: A continuous, unbroken existence with God.

- Reincarnation: The soul’s successive rebirth into new bodies.

While some interpret passages to imply a form of spiritual resurrection, the traditional Christian view holds that after death, the soul either enters eternal communion with God or faces judgment. This contrasts with the belief in reincarnation, where the ‘you’ that makes you ‘you’ is brought back to life after your death, potentially many times.

The Bible presents a linear view of life and afterlife, with death being a transition to a final state, rather than a revolving door of lives.

Kabbalistic Interpretations of Reincarnation

The Emergence of Gilgul neshamot

The Kabbalistic concept of Gilgul neshamot represents the mystical cycle through which souls transmigrate. Gilgul means ‘cycle’ and neshamot is ‘souls’, reflecting the belief that souls return to the physical world to complete their rectification.

This idea found its footing in the 13th century, gaining mainstream acceptance through the influential works of Nachmanides. Lurianic Kabbalah, developed in the 16th century, further elaborated on this concept, linking it to the cosmic process of tikkun, or rectification.

Isaac Luria’s teachings emphasized that reincarnation is not just a personal journey, but also a crucial part of the world’s spiritual restoration.

The metaphorical anthropomorphism of the partzufim in Lurianic thought accentuates the sexual unifications of the redemption process, while reincarnation emerges as a key mechanism in this scheme.

Reincarnation in Jewish thought is not a mere literary motif; it is deeply intertwined with the messianic aspirations and social involvement encouraged by Hasidic Judaism and the Lurianic tradition.

Medieval Jewish Philosophers’ Rejection

During the medieval period, Jewish philosophers like Maimonides approached the concept of the soul with a rationalist perspective, often clashing with the mystical interpretations of Kabbalah.

Maimonides, in particular, was criticized for his philosophical approach, which some Kabbalists felt undermined the esoteric truths of Judaism. His alignment of Talmudic secrets with Aristotelian philosophy was seen as a misinterpretation of the Torah’s true inner meaning.

Medieval Jewish philosophy often found itself at odds with the emerging Kabbalistic views, especially regarding the soul’s journey and reincarnation. The rationalist approach, emphasizing philosophical contemplation, was challenged by Kabbalists who believed in a more mystical and esoteric understanding of Jewish practice.

- Maimonides equated Talmudic secrets with Aristotelian physics and metaphysics.

- Kabbalists believed in an esoteric metaphysics of traditional Jewish practice.

- The debate highlighted the tension between rationalism and mysticism in Jewish thought.

The divergence between medieval Jewish philosophy and Kabbalistic thought represents a fundamental debate over the nature of Jewish spirituality and the soul’s journey.

Isaac Luria’s Centralization of Reincarnation

Isaac Luria, a prominent Kabbalist, revolutionized Jewish mysticism by placing Gilgul neshamot—the cycles of the soul—at the heart of his teachings. His interpretation of Kabbalah emphasized the soul’s journey through reincarnation as a means of cosmic and personal rectification.

Luria’s approach to the Zohar, particularly its most esoteric sections, led to a comprehensive systematization of Kabbalistic thought, where the concept of reincarnation played a pivotal role.

- Luria gathered his disciples, symbolically seating them according to their past lives.

- He reinterpreted the Sephirot, introducing the concept of Partzufim (Divine Personas).

- His teachings on reincarnation became a literary motif in Jewish culture.

Luria’s centralization of reincarnation in Jewish thought marked a significant shift, intertwining the mystical journey of the soul with the broader narrative of spiritual repair and messianic fulfillment.

Christianity’s Rejection of Reincarnation

The Immortality of the Soul in Christian Doctrine

In Christian doctrine, the soul is often viewed as an eternal entity, distinct from the physical body. The soul’s immortality is a cornerstone of Christian belief, suggesting that life continues beyond physical death. This concept has its roots in ancient philosophy and was later adopted by early Christian thinkers.

Christianity inherited the notion of an immortal soul from the Greeks, particularly from the philosophies of Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle. While Plato and Socrates affirmed the soul’s eternal existence, Aristotle believed only a part of the soul, the intellect, was immortal.

The early Church Fathers, including St. Augustine, integrated these ideas into Christian theology, emphasizing the soul’s divine origin and its creation by God.

The soul, as the essence of a person’s being, is not subject to the decay and death that befall the physical body.

St. Augustine described the soul as a ‘rider’ on the body, highlighting the duality yet inseparability of body and soul. In contrast, St. Thomas Aquinas saw the soul as the body’s life force, necessary for individual existence but not wholly independent of the body.

The Finality of Death and Judgment

Christian doctrine emphasizes the finality of death, aligning with the belief that there is a definitive end to human life on earth, followed by judgment.

Death is not a transition to another life but a cessation that awaits divine judgment. This judgment is not immediate upon death but occurs at a time known only to God.

- The concept of Conditional Immortality suggests that eternal life is not inherent but granted by God to the righteous.

- The unrighteous face not an endless cycle of rebirths but a permanent cessation of existence.

The final judgment is the ultimate event where each soul is accounted for, not to be reborn, but to face the consequences of their earthly life.

The idea of a post-mortem existence is not supported by empirical evidence but is a matter of faith, deeply rooted in Christian teachings. The biblical narrative, particularly in Hebrews, suggests that the finality does not come when a person dies but when He who is the Beginning and the End returns and brings salvation.

The Role of Jesus’ Resurrection in Christian Belief

The resurrection of Jesus Christ is a cornerstone of Christian faith, symbolizing the triumph over death and the promise of eternal life. It is through Jesus’ resurrection that Christians find the assurance of their own resurrection and eternal life with God.

This belief is not just a matter of faith but is also supported by numerous accounts in the New Testament, which describe innumerable resurrections, including that of Jesus, Lazarus, and others.

Reincarnation, as a concept, is largely absent from Christian doctrine, which instead emphasizes the finality of death and the subsequent resurrection at the end of times. The Christian narrative posits that after death, the soul faces judgment and the prospect of eternal bliss or damnation, without the cyclical return to earthly life.

- The immortality of the soul

- The final judgment after death

- The singular event of resurrection

The resurrection of Jesus is not merely a historical event but a theological declaration that death is not the end, and that there is hope for life beyond the grave.

Cross-Cultural Beliefs in the Soul’s Journey

Ancient Egyptian and Chinese Concepts of the Soul

The ancient Egyptians and Chinese shared a belief in the duality of the soul, though their understandings diverged in significant ways. The Egyptian ka, akin to breath, stayed close to the deceased’s body, while the ba journeyed to the afterlife.

In contrast, the Chinese recognized a lower soul that perished with death and a higher soul, the hun, which persisted beyond the grave and became the focus of ancestor veneration.

- Egyptian Soul Concepts:

- Ka: Remains with the body

- Ba: Travels to the afterlife

- Chinese Soul Concepts:

- Lower soul: Ceases to exist after death

- Hun: Survives and is worshipped

The interplay between the corporeal and the spiritual in these ancient cultures reflects a complex tapestry of beliefs about the soul’s journey after death. This tapestry provides a rich context for understanding the evolution of soul concepts across different civilizations.

While the Egyptians emphasized proximity to the physical remains, the Chinese placed greater importance on the ongoing spiritual presence of the ancestors, indicating a cultural valuation of legacy and remembrance.

These ancient perspectives on the soul’s journey offer a foundational understanding that informs the broader discussion of reincarnation and the afterlife.

Comparative Analysis of Soul Theories

The concept of the soul has been a subject of contemplation across various cultures and philosophical traditions. Each culture has developed its own understanding of the soul’s nature, its relationship to the body, and its journey after death.

- In Western philosophy, the soul’s existence and nature have been debated since the Middle Ages. René Descartes viewed the soul as a distinct substance interacting with the body, while Benedict de Spinoza saw body and soul as two aspects of a single reality. Immanuel Kant argued that the soul’s existence could not be proven through reason, yet the mind seems compelled to believe in it.

- Eastern philosophies often perceive the soul as an integral part of a cyclical process of rebirth, with the soul’s moral actions influencing its future incarnations.

The diversity in soul theories reflects the profound human desire to understand the essence of life and the mystery of existence.

The soul has been a central topic in the development of ethics and religion, with some philosophers like William James dismissing the soul as a mere collection of psychic phenomena.

This diversity of thought provides a rich tapestry of beliefs that continue to influence contemporary discussions on the afterlife and the immortality of the soul.

Influence of Non-Jewish Beliefs on Jewish Thought

The interplay between Jewish thought and external philosophies has been a subject of scholarly attention, particularly in the context of Kabbalistic interpretations. Jewish mysticism, while rooted in its own traditions, has not been impervious to the currents of non-Jewish intellectual environments.

For instance, the Renaissance period saw a significant cross-pollination of Kabbalistic ideas with Christian Hebraist scholars and occultists, leading to a syncretism that extended into Western esotericism.

Gilgul neshamot (the cycle of souls) is one such concept that, while central to Kabbalistic thought, may have been influenced by the soul theories of surrounding cultures.

This exchange of ideas is evident in the works of influential figures such as Abraham Isaac Kook, who sought to bridge the divide between the sacred and the secular, and the rational and the mystical.

The adaptation of Kabbalistic concepts into non-Jewish frameworks illustrates the fluidity of spiritual ideas across cultural boundaries.

The following list highlights key points of influence:

- The adaptation of Kabbalistic ideas by Christian Hebraists during the Renaissance.

- The impact of Hermeticism and Western esotericism on Jewish mysticism.

- The philosophical exchanges between Jewish and non-Jewish thinkers, such as the dialogues between Kabbalists and Christian scholars.

- The modern reinterpretation of Jewish spirituality in light of 19th-century European rationalism, as seen in the works of Jewish theologians who sought to reconcile traditional mysticism with contemporary thought.

Conclusion

In examining the biblical perspective on the soul and the afterlife, it becomes clear that the concept of reincarnation, as understood in many Eastern religions, does not align with traditional Judeo-Christian teachings.

The Bible presents a narrative of resurrection rather than reincarnation, emphasizing a one-time, transformative event rather than a cyclical process of rebirth. While Kabbalistic Judaism introduced the notion of Gilgul neshamot, or the ‘cycles of the soul,’ this concept remains a point of contention and is not universally accepted within Jewish thought.

Christianity, likewise, focuses on the promise of eternal life through resurrection, as exemplified by the resurrection of Jesus and the hope of a future resurrection for believers. The diversity of beliefs surrounding the soul’s journey after death, whether within the Abrahamic traditions or beyond, underscores the rich tapestry of theological and philosophical interpretations that have sought to understand the ultimate destiny of the human soul.

FAQs;

What does the Bible say about reincarnation?

The Bible does not overtly mention reincarnation. The concept of the soul’s transmigration after death, known as Gilgul neshamot in Kabbalistic tradition, was introduced in the Medieval period and is not found in the Hebrew Bible or classic rabbinic literature.

Is the concept of reincarnation accepted in Christianity?

No, Christianity does not accept reincarnation. Christian doctrine focuses on the immortality of the soul, the finality of death and judgment, and the resurrection of Jesus as central to its belief system.

How did Kabbalistic interpretations influence Jewish thought on reincarnation?

Kabbalistic interpretations, particularly from Isaac Luria, centralized the concept of reincarnation in later Jewish thought. This esoteric tenet of Kabbalah, known as Gilgul neshamot, reinterpreted scriptural passages to explain the cycles of the soul.

Did any Jewish philosophers reject the idea of reincarnation?

Yes, various Medieval Jewish philosophers rejected the idea of reincarnation, including the pre-Kabbalistic Saadia Gaon, who believed that Jews who accepted reincarnation had adopted a non-Jewish belief.

What are some cross-cultural beliefs about the soul’s journey after death?

Ancient cultures such as the Egyptians and the Chinese had dual concepts of the soul, with one aspect surviving death and the other remaining with the body or disappearing. These ideas have influenced a wide range of beliefs about the soul’s journey after death.

Are there any accounts of resurrection in the Bible other than Jesus’?

Yes, the Bible contains several accounts of resurrection besides that of Jesus, including stories in the Old Testament and New Testament of individuals such as Lazarus, Jairus’ daughter, and the young man of Nain.